- Home

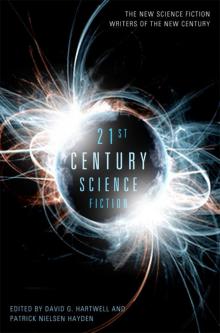

- D B Hartwell

21st Century Science Fiction Page 10

21st Century Science Fiction Read online

Page 10

“No. It was a private conversation.”

“But everyone wants to know why you got out of the car. I had someone from the Financial Times call me about splitting the hits for a tell-all, if you’ll be interviewed. You wouldn’t even need to write up the piece.”

It’s a tempting thought. Easy hits. Many click-throughs. Ad-revenue bonuses. Still, I shake my head. “We did not talk about things that are important for others to hear.”

Janice stares at me as if I am crazy. “You’re not in the position to bargain, Ong. Something happened between the two of you. Something people want to know about. And you need the clicks. Just tell us what happened on your date.”

“I was not on a date. It was an interview.”

“Well then publish the fucking interview and get your average up!”

“No. That is for Kulaap to post, if she wishes. I have something else.”

I show Janice my screen. She leans forward. Her mouth tightens as she reads. For once, her anger is cold. Not the explosion of noise and rage that I expect. “Bluets.” She looks at me. “You need hits and you give them flowers and Walden Pond.”

“I would like to publish this story.”

“No! Hell, no! This is just another story like your butterfly story, and your road contracts story, and your congressional budget story. You won’t get a damn click. It’s pointless. No one will even read it.”

“This is news.”

“Marty went out on a limb for you—” She presses her lips together, reining in her anger. “Fine. It’s up to you, Ong. If you want to destroy your life over Thoreau and flowers, it’s your funeral. We can’t help you if you won’t help yourself. Bottom line, you need fifty thousand readers or I’m sending you back to the third world.”

We look at each other. Two gamblers evaluating one another. Deciding who is betting, and who is bluffing.

I click the “publish” button.

The story launches itself onto the net, announcing itself to the feeds. A minute later a tiny new sun glows in the maelstrom.

Together, Janice and I watch the green spark as it flickers on the screen. Readers turn to the story. Start to ping it and share it amongst themselves, start to register hits on the page. The post grows slightly.

My father gambled on Thoreau. I am my father’s son.

NEAL ASHER Neal Asher Neal Asher is an English writer whose SF began to appear in major magazines and on the lists of large publishing houses in the early years of this century. Often associated with the loosely defined “New Space Opera,” his work is exuberantly imaginative, often violent adventure SF, and displays a flair for the creation of believable aliens. He has in particular invented some of the most astonishing monsters in SF in recent years.

This last talent is well-displayed in “Strood,” a tale in which hyperintelligent aliens have revolutionized human society—up to a point. It is a story about the surprising uses to which species, even sentient ones, put one another.

STROOD

Like a Greek harp standing four meters tall and three wide, its centercurtain body rippling in some unseen wind, the strood shimmered across the park, tendrils groping for me, their stinging pods shiny and bloated. Its voice was the sound of some bedlam ghost in a big empty house: muttering, then bellowing guttural nonsense. Almost instinctively, I ran toward the nearest pathun, with the monster close behind me. The pathun’s curiol matrix reacted with a nacreous flash, displacing us both into a holding cell. I was burned—red skin visible through holes in my shirt—but whether from the strood or the pathun, I don’t know. The strood, its own curiol matrix cut by that of the pathun, lay nearby like a pile of bloody seaweed. I stared about myself at the ten-by-ten box with its floor littered with stones, bones, and pieces of carapace. I really wanted to cry.

“Love! Eat you!” the strood had bellowed. “Eat you! Pain!”

It could have been another of those damned translator problems. The gilst—slapped onto the base of my skull and growing its spines into my brain with agonizing precision—made the latest Pentium Synaptic look like an abacus with most of its beads missing. Unfortunately, with us humans, the gilst is a lot brighter than its host. Mine initially loaded all English on the assumption that I knew the whole of that language, and translating something from say, a pathun, produced stuff from all sorts of obscure vocabularies: scientific, philosophic, sociological, political. All of them. What had that dyspeptic newt with its five ruby eyes and exterior mobile intestine said to me shortly after my arrival?

“Translocate fifteen degrees sub-axial to hemispherical concrescence of poly-carbon interface.”

I’d asked where the orientating machine was, and it could have just pointed to the lump on the nearby wall and said, “Over there.”

After forty-six hours in the space station, I was managing, by the feedback techniques that load into your mind like an instruction manual the moment the spines begin to dig in, to limit the gilst’s vocabulary to my feeble one, and thought I’d got a handle on it, until my encounter with the strood. I’d even managed to stop it translating what the occasional patronizing mugull would ask me every time I stopped to gape at some extraordinary sight, as “Is one’s discombobulation requiring pellucidity?” I knew the words, but couldn’t shake the feeling that either the translator or the mugull was having a joke at my expense. All not too good when really I had no time to spare for being lost on the station—I wanted to see so much before I died.

The odds of survival, before the pathun lander set down on the Antarctic, had been one-in-ten for surviving more than five years. My lung cancer, lodged in both lungs, considerably reduced those odds for me. By the time pathun technology started filtering out, my cancer had metastized, sending out scouts to inspect other real estate in my body. And when I finally began to receive any benefits of that technology, my cancer had established a burgeoning population in my liver and colonies in other places too numerous to mention.

“We cannot help you,” the mugull doctor had told me, as it floated a meter off the ground in the pathun hospital on the Isle of Wight. Hospitals like this one were springing up all over Earth, like Medicins Sans Frontières establishments in some Third World backwater. Mostly run by mugulls meticulously explaining to our witchdoctors where they were going wrong. To the more worshipful of the population, that name might as well have stood for, “alien angels like translucent manta rays.” But the contraction of “mucus gull” that became their name is more apposite for the majority, and their patronizing attitude comes hard from something that looks like a floating sheet of veined snot with two beaks, black button eyes, and a transparent nematode body smelling of burning bacon.

“Pardon?” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing: they were miracle workers who had crossed mind-numbing distances to come here to employ their magical technologies. This mugull explained it to me in perfect English, without a translator. It, and others like it, had managed to create those nanofactories that sat in the liver pumping out DNA repair nanomachines. Now this was okay if you got your nactor before your DNA was damaged. It meant eternal youth, so long as you avoided stepping in front of a truck. But, for me, there was just too much damage already, so my nactor couldn’t distinguish patient from disease.

“But . . . you will be able to cure me?” I still couldn’t quite take it in.

“No.” A flat reply. And with that, I began to understand, began to put together facts I had thus far chosen to ignore.

People were still dying in huge numbers all across Earth, and the alien doctors had to prioritize. In Britain, it’s mainly the wonderful bugs tenderly nurtured by our national health system to be resistant to just about every antibiotic going. In fact, the mugulls had some problems getting people into their hospitals in the British Isles, because over the last decade, hospitals had become more dangerous to the sick than anywhere else. Go in to have an ingrown toenail removed; MRSA or a variant later, and you’re down the road in a hermetically sealed plastic coffin. However, most

alien resources were going into the same countries as Frontières went to: to battle a daily death rate, numbered in tens of thousands, from new air-transmitted HIVs, rampant Ebola, and that new tuberculosis that can eat your lungs in about four days. And I don’t know if they are winning.

“Please . . . you’ve got to help me.”

No good. I knew the statistics, and, like so many, had been an avid student of all things alien ever since their arrival. Even by stopping to talk to me as its curiol matrix wafted it from research ward to ward, the mugull might be sacrificing other lives. Resources again. They had down to an art what our own crippled health service had not been able to apply in fact without outcry: if three people have a terminal disease and you have the resources to save only two of them, that’s what you do, you don’t ruin it in a futile attempt to save them all. This mugull, applying all its skill and available technologies, could certainly save me, it could take my body apart and rebuild it cell by cell if necessary, but meanwhile, ten, twenty, a thousand other people with less serious, but no less terminal conditions, would die.

“Here is your ticket,” it said, and something spat out of its curiol matrix to land on my bed as it wafted away.

I stared down at the yellow ten-centimeter disk. Thousands of these had been issued, and governments had tried to control whom to, and why. Mattered not a damn to any of the aliens; they gave them to those they considered fit, and only the people they were intended for could use them . . . to travel offworld. I guess it was my consolation prize.

A mugull autosurgeon implanted a cybernetic assister frame. This enabled me to get out of bed and head for the shuttle platform moored off the Kent coast. There wasn’t any pain at first, as the surgeon had used a nerve-block that took its time to wear off, but I felt about as together as rotten lace. As the nerve-block wore off, I went back onto my inhalers, and patches where the bone cancer was worst, and a cornucopia of pills.

On the shuttle, which basically looked like a train carriage, I attempted to concentrate on some of the alien identification charts I’d loaded into my notescreen, but the nagging pain and perpetual weariness made it difficult for me to concentrate. There was as odd a mix of people around me as you’d find on any aircraft: some woman with a baby in a papoose; a couple of suited heavies who could have been government, Mafia, or stockbrokers; and others. Just ahead of me was a group of two women and three men who, with plummy voices and scruffy-bordering-on-punk clothing—that upper-middle-class lefty look favored by most students—had to be the BBC documentary team I’d heard about. This was confirmed for me when one of the men removed a prominently labeled vidcam to film the non-human passengers. These were two mugulls and a pathun—the latter a creature like a two-meter woodlouse, front section folded upright with a massively complex head capable of revolving three-sixty, and a flat back onto which a second row of multiple limbs folded. As far as tool-using went, nature had provided pathuns with a work surface, clamping hands with the strength of a hydraulic vise, and other hands with digits fine as hairs. The guy with the vidcam lowered it after a while and turned to look around. Then he focused on me.

“Hi, I’m Nigel,” he held out a hand, which I reluctantly shook. “What are you up for?”

I considered telling him to mind his own business, but then thought I could do with all the help I could get. “I’m going to the system base to die.”

Within seconds, Nigel had his vidcam in my face, and one of his companions, Julia, had exchanged places with the passenger in the seat adjacent to me, and was pumping me with ersatz sincerity about how it felt to be dying, then attempting to stir some shit about the mugulls being unable to treat me on Earth. The interview lasted nearly an hour, and I knew they would cut and shape it to say whatever they wanted it to say.

When it was over, I returned my attention to the pathun, who I was sure had turned its head slightly to watch and listen in, though why I couldn’t imagine. Perhaps it was interested in the primitive equipment the crew used. Apparently, one of these HG (heavy gravity) creatures, while being shown around Silicon Valley, accidentally rested its full weight on someone’s laptop computer—think about dropping a barbell on a matchbox and you get the idea—then, without tools, repaired it in under an hour. And as if that wasn’t miraculous enough, the computer’s owner had discovered that the laptop’s hard disk storage had risen from four hundred gigabytes to four terabytes. I would have said the story was apocryphal, but the laptop is now in the Smithsonian.

The shuttle docked at Eulogy Station, and the pathun disembarked first, which is just the way it is. Equality is a fine notion; the reality is that they’ve been knocking around the galaxy for half a million years. Pathuns are as far in advance of the other aliens as we are in advance of jellyfish, which makes you wonder where humans rate on their scale. As the alien went past me, heading for the door, I felt the slight air shift caused by its curiol matrix—that technology enabling other aliens, like mugulls, creatures whose home environment is an interstellar gas cloud not far above absolute zero, to live on the surface of Earth and easily manipulate their surroundings. Call it a force field, but it’s much more than that. Another story about pathuns demonstrates some of what they can do with their curiol matrices:

All sorts of religious fanatic lunatic idiotic groups immediately, of course, considered superior aliens the cause of their woes, and valid targets, so it was only a week into the first alien walkabout that the first suicide bomber tried to take out a pathun amid a crowd. He detonated his device, but an invisible cylinder enclosed him and the plastique slow-burned—not a pretty sight. Other assassination attempts met with various suitable responses. The sharpshooter with his scoped rifle got the bullet he fired back through the scope and into his head. The bomber in Spain just disappeared along with his car, only to reappear, still behind the wheel, traveling at mach four down on top of the farmhouse his fellow Basque terrorists had made their base. Thereafter, attempts started to drop off, not because of any reduction in terrorist lunacy, but because of a huge increase in security when a balek (those floating LGAs that look like great big apple cores) off-handedly mentioned what incredible restraint the pathuns—beings capable of translocating planet Earth into its own sun—were showing.

From Eulogy Station, it was, in both alien and my own terms, just a short step to the system base. The gate was just a big ring in one of the plazas of Eulogy, and you just stepped through it and you were there. The base, a giant stack of different-sized disks nine hundred and forty kilometers from top to bottom, orbited Jupiter. After translocating from some system eighty light-years away to our Oort Cloud, it had traveled to here at half the speed of light while the contact ships headed to Earth. Apparently, we had been ripe for contact: bright enough to understand what was happening, but stupid enough for our civilization not to end up imploding when confronted by such omnipotence.

In the system base, I began to find my way around, guided by an orientation download to my notescreen, and it was only then that I began to notice stroods everywhere. I had only ever seen pictures before, and, as far as I knew, none had ever been to Earth. But why were there so many thousands here, now? Then, of course, I allowed myself a hollow laugh. What the hell did it matter to me? Still, I asked Julia and Nigel when I ran into them again.

“According to our researcher, they’re pretty low on the species scale and only space-faring because of pathun intervention.” Julia studied her note screen—uncomfortable being the interviewee. Nigel was leaning over the rail behind her, filming down an immense metallic slope on which large limpetlike creatures clung sleeping in their thousands: stroods in their somnolent form.

Julia continued, “Some of the other races regard stroods as pathun pets, but then, we’re not regarded much higher by many of them.”

“But why so many thousands here?” I asked.

Angrily, she gestured at the slope. “I’ve asked, and every time, I’ve been told to go and ask the pathuns. They ignore us, you know—far too bus

y about their important tasks.”

I resisted the impulse to point out that creatures capable of crossing the galaxy perhaps did not rank the endless creation of media pap very high. I succumbed then to one more “brief” interview before managing to slip away, and then, losing my way to my designated hotel, ended up in one of the parks, aware that a strood was following me . . . .

Sitting in the holding cell, I eyed the monster and hoped that its curiol matrix wouldn’t start up again, as in here I had nowhere to run, and, being the contacted species, no curiol matrix of my own. The environment of a system station is that of the system species, us, so we didn’t need the matrix for survival, and anyway, you don’t give the kiddies sharp objects to play with right away. I was beginning to wonder if maybe running at that pathun had been such a bright idea, when I was abruptly translocated again, and found myself stumbling into the lobby of an apparently ordinary-looking hotel. I did a double take, then turned round and walked out through the revolving doors and looked around. Yep, an apparently normal city street—except for Jupiter in the sky. This was the area I’d been trying to find before my confrontation with the strood: the human section, a nice homey, normal-seeming base for us so we wouldn’t get too confused or frightened. I went back into the hotel, limping a bit now, despite the assister frame, and wheezing because I’d lost my inhaler, and the patches and pills were beginning to wear off.

“David Hall,” I said at the front desk. “I have a reservation.”

The automaton dipped its polished chrome ant’s head and eyed my damaged clothing, then it checked its screen, and after a moment it handed—or rather, clawed—over a key card. I headed for the elevator and soon found myself in the kind of room I’d never been able to afford on Earth, my luggage already stacked beside my bed, and a welcome pack on a nearby table. I opened the half bottle of champagne and began chugging it down as I walked out onto the balcony. Now what?

21st Century Science Fiction

21st Century Science Fiction